BESS LOMAX HAWES , SONGMAKERS’ MATRIARCH

By Annie Reeves

Bess Lomax Hawes was born on January 21, 1921, in Austin, Texas. She was the daughter of John Avery Lomax and Bess Bauman-Brown Lomax, and the sister of famed folklorist Alan Lomax. Her father served as president of the American Folklore Society twice and was Honorary Curator of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress during 13 of Bess’s early years. Because of her father’s interests and connections, Bess’s childhood was steeped in folk music. But it was her mother who taught her to play the piano, at which she excelled. That success subsequently encouraged her to take up the guitar.

Education and Early Career

At 15, Bess entered the University of Texas. The next year, she helped her father, brother, and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger (Pete’s half-sister) with their book, Our Singing Country. She graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a sociology degree in 1941. Later, in the 1960s, she would become one of the first students to receive an MA in folklore at UC Berkeley.

Bess moved to New York City in the early 1940s, where she became active in the growing folk scene. Intermittently she performed with the Almanac Singers, which included Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie; Woody taught her to play the mandolin. In 1943, she married artist and fellow Almanac singer, Baldwin “Butch” Hawes.

During World War II, Bess worked for the War Office preparing radio broadcasts for our overseas troops. After the war, she and her family moved to Boston, where she wrote a number of satiric political songs, including—with Jacqueline Steiner—”Charlie on the MTA” (1949), which was adapted from a local political campaign jingle. The song would become a big hit for the Kingston Trio ten years afterward.

While in Boston, Bess’s three children attended a cooperative, progressive nursery school. Bess often took her guitar there to perform for the toddlers. Some of the parents asked her to teach them how to play guitar, banjo, and mandolin. Bess agreed, charging them one dollar per person for each lesson, which lasted several hours. She kept half to pay for a babysitter and donated the other half to the nursery school. Her classes quickly became very popular.

A Master Teacher Emerges

As she gave these classes, Bess developed a method of teaching guitar to groups of 30 to 40 people at a time, for which she eventually became famous. Over the years, she would wind up teaching thousands of people. Many of her students became guitar teachers themselves, passing on her method and her love of folk music. This in turn helped to stoke the folk music revival of the 1950s and ’60s.

In the 1950s, Bess moved to California, where she taught UCLA Extension courses in guitar, banjo, mandolin, and folk singing. Later she taught at the Idyllwild summer arts program and at San Fernando Valley State College (now Cal State University, Northridge). She also performed in local clubs and at some large folk festivals, such as the Newport Folk Festival and the Berkeley Folk Festival.

Bess explained her teaching method’s popularity by saying, “Students learning guitar individually can get intimidated, because they can hear their own mistakes. In a group, the students feel bolder about playing, take more risks, enjoy it more, and feel part of something bigger, which sounds better, anyway.” [Quoted in Peter Dreier’s “Remembering Bess Lomax Hawes,” Huffington Post, Nov. 30, 2009.]

The Songmakers Connection

A Hawes student named Nick Steed organized a small song circle to practice what they were learning. His initial group of three grew to become the West Valley Guitar Group. (Woody Guthrie’s address in the New Jersey hospital where he lived from 1956-1961 was penciled into a roster of the West Valley Guitar group found in the Songmakers archives.) This group then combined with a group called People’s Songs West, which played folk music in LA parks. The new musical coalition took the name Songmakers of California; its purpose was to promote American folk music and provide a forum for original folk songs. For ten years thereafter, Bill Wolff produced the first Songmakers newsletter, “The Almanac.”

Another of Bess’s students, Mary Ellen Clark, became a well-known guitar teacher as well as a member of Songmakers. Mary Ellen and a number of her students of are still Songmakers today [October 2020]. The late ’50s and early ’60s were fruitful times for Songmakers, with several ongoing hoots along with performing, writing, teaching, and hoot-leading workshops.

Above – Bess Hawes and Ann Howitt

Impressive Later Career

Meanwhile, in 1968, Bess Lomax Hawes was named Associate Professor of Anthropology at San Fernando Valley State College and, later, head of the Anthropology Department. While there, Bess created an extensive archive of folk songs collected by students of hers in Los Angeles and abroad. She also served as president of the California Folklore Society and vice president of the American Folklore Society.

Sadly, Bess’s husband Butch died in 1971. But she still had many years of service to give to her passion.

In 1975, Bess became an administrative official of the Smithsonian Institution, where she played a major role in organizing the Smithsonian’s 1976 Bicentennial Festival of Traditional Folk Arts. In 1977, she was appointed as the first director of the Folk and Traditional Arts Program at the National Endowment for the Arts. There she set up the National Heritage Fellowships, which recognize traditional artists and performers. During her tenure as director, funding for folk arts rose from about $100,000 to $4 million [per year, I assume, though I haven’t been able to confirm this], and 50 state or territorial folk arts programs were started. The Smithsonian’s website says she accomplished this “…with a vast knowledge of America’s diverse traditions, the discipline of a savvy strategist, an empathy born of experience for cultural work, and a personal reservoir of good grace.”

Speaking about the fellowships she created, Bess told The Washington Post in 1983, “These individuals are the people who’ve been pushed up by the traditions… It’s extremely important for the psychic health and well-being of Americans to maintain all of these little regional distinctions, to establish a cultural pluralism. It’s like my brother folklorist Alan Lomax wrote one time: if the cultural gray-out continues around the world, pretty soon there will be no place worth visiting … and no particular reason to stay home, either.”

After following her bliss by working tirelessly for decades on behalf of folk music and arts, Bess finally retired in 1992.

Books, Films, and Other Achievements

In addition to everything mentioned above, Bess Lomax Hawes received an honorary doctorate from the University of North Carolina in 1993. That same year, President Bill Clinton awarded her the National Medal of Arts.

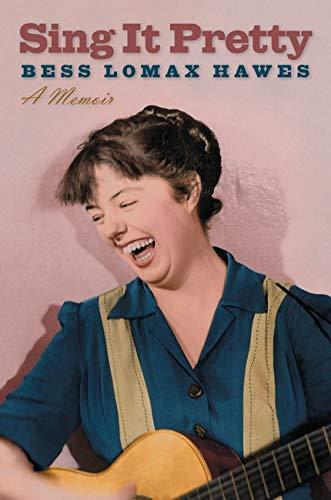

She continued to speak and consult internationally on issues of folklore, public policy, and “cultural continuity.” An NEA traditional arts award is named in her honor. The Illinois University Press published her memoir, Sing It Pretty, in 2008.

Of songs Bess wrote or cowrote, by far her best known is “MTA.” I was unable to find information on any solo albums she recorded, though she contributed to many folk music collections. With the Almanac Singers, for example, she appears on “Songs for John Doe” and “Talking Union.” In 1940, she contributed to “Songs of the Lincoln Battalion” along with Pete Seeger, Tom Glazer, and Butch Hawes. The album presents “the songs of the men who left home and safety behind them in 1937 to fight Fascism” in Spain. She also sang on the Folkways Records albums “Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs” and “Spanish Civil War,” as well as others that were compiled in later years.

Bess has several books to her credit. In addition to her early collaboration on Our Singing Country and the personal memoir mentioned above, Bess cowrote, with Bessie Smith Jones, Step it Down: Games, Plays, Songs, and Stories from the Afro-American Heritage. She also cowrote, with her brother Alan, There’s a Brown Girl in the Ring. What’s more, she made four documentary films while at San Fernando Valley State: “Georgia Sea Island Singers,” “Buckdancer,” “Pizza Pizza Daddy-O” (about African-American children’s singing games), and “Say, Old Man, Can You Play the Fiddle?”

On November 27, 2009 at age 88, Bess Lomax Hawes died in Portland, Oregon, after a stroke. Hers was truly a musical life well lived and a Songmakers’ ancestor to be proud of!

Photo below: The cover of Bess’s memoir, Sing It Pretty.

More on Bess’ connection to Songmakers by Linnea Richards